American Way of Birth, Costliest in the World

Josh Haner/The New York Times

“I feel like I’m in a used-car lot.” Renée Martin, who, with her husband, is paying for her maternity care out of pocket.

By ELISABETH ROSENTHAL | Published: June 30, 2013

“Throughout this article, readers have shared their experiences by responding to questions about their perspective on pregnancy care. Comments are now closed, but you may explore the responses received.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, reporter

LACONIA, N.H. — Seven months pregnant, at a time when most expectant couples are stockpiling diapers and choosing car seats, Renée Martin was struggling with bigger purchases.

At a prenatal class in March, she was told about epiduralanesthesia and was given the option of using a birthing tub during labor. To each offer, she had one gnawing question: “How much is that going to cost?”

Though Ms. Martin, 31, and her husband, Mark Willett, are both professionals with health insurance, her current policy does not cover maternity care. So the couple had to approach the nine months that led to the birth of their daughter in May like an extended shopping trip though the American health care bazaar, sorting through an array of maternity services that most often have no clear price and — with no insurer to haggle on their behalf — trying to negotiate discounts from hospitals and doctors.

When she became pregnant, Ms. Martin called her local hospital inquiring about the price of maternity care; the finance office at first said it did not know, and then gave her a range of $4,000 to $45,000. “It was unreal,” Ms. Martin said. “I was like, How could you not know this? You’re a hospital.”

Midway through her pregnancy, she fought for a deep discount on a $935 bill for anultrasound, arguing that she had already paid a radiologist $256 to read the scan, which took only 20 minutes of a technician’s time using a machine that had been bought years ago. She ended up paying $655. “I feel like I’m in a used-car lot,” said Ms. Martin, a former art gallery manager who is starting graduate school in the fall.

Like Ms. Martin, plenty of other pregnant women are getting sticker shock in the United States, where charges for delivery have about tripled since 1996, according to an analysis done for The New York Times by Truven Health Analytics. Childbirth in the United States is uniquely expensive, and maternity and newborn care constitute thesingle biggest category of hospital payouts for most commercial insurers and state Medicaid programs. The cumulative costs of approximately four million annual births is well over $50 billion.

And though maternity care costs far less in other developed countries than it does in the United States, studies show that their citizens do not have less access to care or to high-tech care during pregnancy than Americans.

“It’s not primarily that we get a different bundle of services when we have a baby,” said Gerard Anderson, an economist at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health who studies international health costs. “It’s that we pay individually for each service and pay more for the services we receive.”

Those payment incentives for providers also mean that American women with normal pregnancies tend to get more of everything, necessary or not, from blood tests to ultrasound scans, said Katy Kozhimannil, a professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health who studies the cost of women’s health care.

Financially, they suffer the consequences. In 2011, 62 percent of women in the United States covered by private plans that were not obtained through an employer lacked maternity coverage, like Ms. Martin. But even many women with coverage are feeling the pinch as insurers demand higher co-payments and deductibles and exclude many pregnancy-related services.

From 2004 to 2010, the prices that insurers paid for childbirth — one of the most universal medical encounters — rose 49 percent for vaginal births and 41 percent for Caesarean sections in the United States, with average out-of-pocket costs rising fourfold, according to a recent report by Truven that was commissioned by three health care groups. The average total price charged for pregnancy and newborn care was about $30,000 for a vaginal delivery and $50,000 for a C-section, with commercial insurers paying out an average of $18,329 and $27,866, the report found.

Women with insurance pay out of pocket an average of $3,400, according to a survey by Childbirth Connection, one of the groups behind the maternity costs report. Two decades ago, women typically paid nothing other than a small fee if they opted for a private hospital room or television.

Only in America

In most other developed countries, comprehensive maternity care is free or cheap for all, considered vital to ensuring the health of future generations.

Ireland, for example, guarantees free maternity care at public hospitals, though women can opt for private deliveries for a fee. The average price spent on a normal vaginal delivery tops out at about $4,000 in Switzerland, France and the Netherlands, where charges are limited through a combination of regulation and price setting; mothers pay little of that cost.

The chasm in price is true even though new mothers in France and elsewhere often remain in the hospital for nearly a week to heal and learn to breast-feed, while American women tend to be discharged a day or two after birth, since insurers do not pay costs for anything that is not considered medically necessary.

Only in the United States is pregnancy generally billed item by item, a practice that has spiraled in the past decade, doctors say. No item is too small. Charges that 20 years ago were lumped together and covered under the general hospital fee are now broken out, leading to more bills and inflated costs. There are separate fees for the delivery room, the birthing tub and each night in a semiprivate hospital room, typically thousands of dollars. Even removing the placenta can be coded as a separate charge.

Each new test is a new source of revenue, from the hundreds of dollars billed for the simple blood typing required before each delivery to the $20 or so for the splash of gentian violet used as a disinfectant on the umbilical cord (Walgreens’ price per bottle: $2.59). Obstetricians, who used to do routine tests like ultrasounds in their office as part of their flat fee, now charge for the service or farm out such testing to radiologists, whose rates are far higher.

Add up the bills, and the total is startling. “We’ve created incentives that encourage more expensive care, rather than care that is good for the mother,” said Maureen Corry, the executive director of Childbirth Connection.

In almost all other developed countries, hospitals and doctors receive a flat fee for the care of an expectant mother, and while there are guidelines, women have a broad array of choices. “There are no bills, and a hospital doesn’t get paid for doing specific things,” said Charlotte Overgaard, an assistant professor of public health at Aalborg University in Denmark. “If a woman wants acupuncture, an epidural or birth in water, that’s what she’ll get.”

Despite its lavish spending, the United States has one of the highest rates of both infant and maternal death among industrialized nations, although the fact that poor and uninsured women and those whose insurance does not cover childbirth have trouble getting or paying for prenatal care contributes to those figures.

Some social factors drive up the expenses. Mothers are now older than ever before, and therefore more likely to require or request more expensive prenatal testing. And obstetricians face the highest malpractice risks among physicians and pay hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for insurance, fostering a “more is safer” attitude.

But less than 25 percent of America’s high payments for pregnancy typically go to obstetricians, and they often charge a flat fee for their nine months of care, no matter how many visits are needed, said Dr. Robert Palmer, the chairman of the committee for health economics and coding at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. That fee can range from a high of more than $8,000 for a vaginal delivery in Manhattan to under $4,000 in Denver, according to Fair Health, which collects health care data.

Rather it is the piecemeal way Americans pay for this life event that encourages overtreatment and overspending, said Dr. Kozhimannil, the Minnesota professor. Recent studies have found that more than 30 percent of American women have Caesarean sections or have labor induced with drugs — far higher numbers than those of other developed countries and far above rates that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists considers necessary.

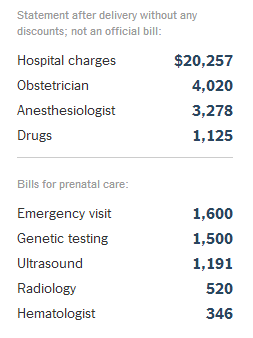

During the course of her relatively uneventful pregnancy, Ms. Martin was charged one by one for lab tests, scans and emergency room visits that were not included in the doctor’s or the hospital’s fee. During her seventh month, she described one week’s experience: “I have high glucose, and I tried to take a three-hour test yesterday and threw up all over the lab. So I’m probably going to get charged for that. And my platelets are low, so I’m going to have to see a hematologist. So I’m going to get charged for that.”

She sighed and put her head in her hands. “Welcome to my world,” she said.

Extras Add Up

Though Ms. Martin has yet to receive her final bills, other couples describe being blindsided by enormous expenses. After discovering that their insurance did not cover pregnancy when the first ultrasound bill was denied last year, Chris Sullivan and his wife, both freelance translators in Pennsylvania, bought a $4,000 pregnancy package from Delaware County Memorial Hospital; a few hospitals around the country are starting to offer such packages to those patients paying themselves.

The couple knew that price did not cover extras like amniocentesis, a test for genetic defects, or an epidural during labor. So when the obstetrician suggested an additional fetal heart scan to check for abnormalities, they were careful to ask about price and got an estimate of $265. Performed by a specialist from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, it took 30 minutes and showed no problems — but generated a bill of $2,775.

“All of a sudden I have a bill that’s as much as I make in a month, and is more than 10 times what I’d been quoted,” Mr. Sullivan said. “I don’t know how I could have been a better consumer, I asked for a quote. Then I get this six-part bill.” After months of disputing the large discrepancy between the estimate and the bill, the hospital honored the estimate.

Christopher Gregory/The New York Times

“Most insurance companies wouldn’t blink at my bill, but it was absurd.” Dr. Marguerite Duane, who questioned line items on her hospital bill.

Mr. Sullivan noted that the couple ended up paying $750 for an epidural, a procedure that has a list price of about $100 in his wife’s native Germany.

Even women with the best insurance can still encounter high prices. After her daughter was born five years ago, Dr. Marguerite Duane, 42, was flabbergasted by the line items on the bills, many for blood tests she said were unnecessary and medicines she never received. She and her husband, Dr. Kenneth Lin, both associate professors of family medicine at Georgetown Medical School, had delivered babies in their early years of practice.

So when she became pregnant again in 2011, she decided to be more assertive about holding down costs. After a routine ultrasound scan at 20 weeks showed a healthy baby, she refused to go back for weekly follow-up scans that the radiologist suggested during the last months of her pregnancy even though medical guidelines do not recommend them. When in the hospital for the delivery of her son Ellis in February, she kept a list of every medicine and every item she received.

Though she delivered Ellis with a midwife 12 minutes after arriving at the hospital and was home the next day, the hospital bill alone was more than $6,000, and her insurance co-payment was about $1,500. Her first two pregnancies, both more than five years ago, were fully covered by federal government insurance because her husband worked for the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.

“Most insurance companies wouldn’t blink at my bill, but it was absurd — it was the least medical delivery in history,” said Dr. Duane, who is taking a break from practice to stay home with her children. “There were no meds. I had no anesthesia. He was never in the nursery. I even brought my own heating pad. I tried to get an explanation, but there were items like ‘maternity supplies.’ What was that? A diaper?”

Ms. Martin is similarly well positioned to be an expert consumer of health care. She administered the health plan for a large art gallery she managed in Los Angeles before marrying and moving to Vermont in 2011 to enroll in a year of pre-med classes at the University of Vermont. She has a scholarship this fall for a master’s degree program at Vanderbilt University’s Center for Medicine, Health and Society, and then she plans to go on to medical school. Her father-in-law is a pediatrician.

She and her husband, who works for a small music licensing company that does not provide insurance, hoped to start their family during the year they were covered by university insurance in Vermont, she said, but “nature didn’t cooperate.”

Then they moved to the New Hampshire summer resort of Laconia, her husband’s hometown, for a year before she started the grind of medical training. But in New Hampshire, they discovered, health insurance they could buy on the individual market did not cover maternity care without the purchase of an additional “pregnancy rider” for $800 a month. With their limited finances and unsuccessful efforts at conceiving, it seemed an unwise, if not impossible, investment.

Soon after buying insurance coverage without the rider for $450 a month, Ms. Martin discovered she was pregnant. Her elation was quickly undercut by worry.

“We’re not poor. We pay our bills. We have medical insurance. We’re not looking for a handout,” Ms. Martin said, noting that her husband makes too much money for her to qualify for Medicaid or other subsidized programs for low-income women. “The hospital is doing what it can. Our doctors are taking wonderful care of us. But the economics of this system are a mess.”

Not knowing whether the pregnancy would fall at the $4,000 or $45,000 end of the range the hospital cited, the couple had a hard time budgeting their finances or imagining their future. The hospital promised a 30 percent discount on its final bill. “I’m trying not to be stressed, but it’s really stressful,” Ms. Martin said as her due date approached.

Package Deals

With costs spiraling, some hospitals are starting to offer all-inclusive rates for pregnancy. Maricopa Medical Center, a public hospital in Phoenix, began offering uninsured patients a comprehensive package two years ago. “Making women choose during labor whether you want to pay $1,000 for an epidural, that didn’t seem right,” said Dr. Dean Coonrod, the hospital’s chief of obstetrics and gynecology.

The hospital charges $3,850 for a vaginal delivery, with or without an epidural, and $5,600 for a planned C-section — prices that include standard hospital, doctors’ and testing fees. To set the price, the hospital — which breaks even on maternity care and whose doctors are on salaries — calculated the average payment it gets from all insurers. While Dr. Coonrod said the hospital might lose a bit of money, he saw other benefits in a market where everyone will have insurance in just a few years: mothers tend to feel allegiance to the place they give birth to their babies and might seek other care at Maricopa in the future.

Laura Segall for The New York Times

“Making women choose during labor whether you want to pay $1,000 for an epidural, that didn’t seem right.” Dr. Dean Coonrod, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix

The Catalyst for Payment Reform, a California policy group, has proposed that all hospitals should offer such bundled prices and that rates should be the same, no matter the type of delivery. It suggests that $8,000 might be a reasonable starting point. But that may be hard to imagine in markets like New York City, where $8,000 is less than many private doctors charge for their fees alone.

One factor that has helped keep costs down in other developed countries is the extensive use of midwives, who perform the bulk of prenatal examinations and even simple deliveries; obstetricians are regarded as specialists who step in only when there is risk or need. Sixty-eight percent of births are attended by a midwife in Britain and 45 percent in the Netherlands, compared with 8 percent in the United States. In Germany, midwives were paid less than $325 for an 11-hour delivery and about $30 for an office visit in 2011.

Dr. Palmer of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists acknowledged the preference for what he called “medicalized” deliveries in the United States, with IVs, anesthesia and a proliferation of costly ultrasounds. He said the organization was working to define standards for the scans.

To control costs in the United States, patients may also have to alter their expectations, including the presence of an obstetrician at every prenatal visit and delivery. “It’s amazing how much patients buy into our tendency to do a lot of tests,” said Eugene Declercq, a professor at Boston University who studies international variations in pregnancy. “We’ve met the problem, and it’s us.”

Starting next year, insurance policies will be required under the Affordable Care Act to include maternity coverage, so no woman should be left paying entirely on her own, like Ms. Martin. But the law is not explicit about what services must be included in that coverage. “Exactly what that means is the crux of the issue,” Dr. Kozhimannil said.

If the high costs of maternity care are not reined in, it could break the bank for many states, which bear the brunt of Medicaid payouts. Medicaid, the federal-state government health insurance program for the poor, pays for more than 40 percent of all births nationally, including more than half of those in Louisiana and Texas. But even Medicaid, whose payments are regarded as so low that many doctors refuse to take patients covered under the program, paid an average of $9,131 for vaginal births and $13,590 for Caesarean deliveries in 2011.

Insured women are still getting the recommended prenatal care, despite rising out-of-pocket costs, according to a recent study. But that does not mean they are not feeling the strain, said Dr. Kozhimannil, the study’s lead author. The average amount of savings among pregnant women in the study was $3,000 to $5,000. “People will find ways to scrape by for medical care for their new baby, but are young mothers taking care of themselves? And what happens when they need to start buying diapers?” she asked. “Something’s got to give.”

Ms. Martin, who busied herself making toys as her due date neared, could not stop fretting about the potential cost of a complicated delivery. “I know that a C-section could ruin us financially,” she said.

On May 25, she had a healthy daughter, Isla Daisy, born by vaginal delivery. Mother and daughter went home two days later.

She and her husband are both overjoyed and tired. And, she said, they are “dreading” the bills, which she estimates will be over $32,000 before negotiations begin. Her labor was induced, which required intense monitoring, and she also had an epidural.

“We’re bracing for it,” she said.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: July 2, 2013

An article on Monday about the high cost of maternity and newborn care in the United States misstated the number of years ago that Dr. Marguerite Duane’s daughter was born. It was five years ago, not seven. The article also misidentified which of Dr. Duane’s sons was born in February. He is Ellis — not Isaac, who is her older son.