Alan Watts on Money vs. Wealth

I started by quoting sections of the article and then halfway through I realized I was quoting every other paragraph, so here’s the whole article:

“by Maria Popova

“The moral challenge and the grim problem we face is that the life of affluence and pleasure requires exact discipline and high imagination.”

“What would you do if money was no object?”pioneering British philosopher Alan Watts, who popularized Zen teachings in the West, asked inone of his most memorable lectures. And yet, despite our best efforts not to worry about it, money is an object — so much so that it renders the question all the more urgent and pressing today, in our age of growing corporate greed coupled with increasing income inequality. Watts revisits the issue in greater depth in an essay titled “Wealth Versus Money,” found in the altogether fantastic 1970 anthology Does It Matter? Essays on Man’s Relation to Materiality(public library) — a poignant exploration of our tendency to confuse money with wealth, a manifestation of our more general inclination to mistake symbol for reality, which Watts considers “the peculiar and perhaps fatal fallacy of civilization.”

“What would you do if money was no object?”pioneering British philosopher Alan Watts, who popularized Zen teachings in the West, asked inone of his most memorable lectures. And yet, despite our best efforts not to worry about it, money is an object — so much so that it renders the question all the more urgent and pressing today, in our age of growing corporate greed coupled with increasing income inequality. Watts revisits the issue in greater depth in an essay titled “Wealth Versus Money,” found in the altogether fantastic 1970 anthology Does It Matter? Essays on Man’s Relation to Materiality(public library) — a poignant exploration of our tendency to confuse money with wealth, a manifestation of our more general inclination to mistake symbol for reality, which Watts considers “the peculiar and perhaps fatal fallacy of civilization.”

Watts writes:

Civilization, comprising all the achievements of art and science, technology and industry, is the result of man’s invention and manipulation of symbols — of words, letters, numbers, formulas and concepts, and of such social institutions as universally accepted clocks and rulers, scales and timetables, schedules and laws. By these means, we measure, predict, and control the behavior of the human and natural worlds — and with such startling apparent success that the trick goes to our heads. All too easily, we confuse the world as we symbolize it with the world as it is.

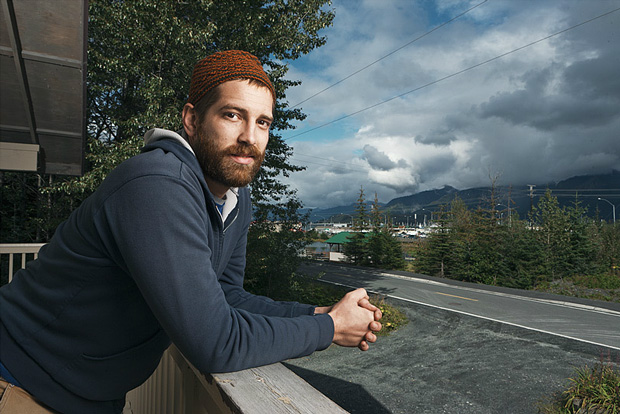

Alan Watts, early 1970s (Image courtesy of Everett Collection)

Among our most toxic symbol-as-reality tricks springs from the concept, use, and pursuit of money:

Money is a way of measuring wealth but is not wealth in itself. A chest of gold coins or a fat wallet of bills is of no use whatsoever to a wrecked sailor alone on a raft. He needs real wealth, in the form of a fishing rod, a compass, an outboard motor with gas, and a female companion. But this ingrained and archaic confusion of money with wealth is now the main reason we are not going ahead full tilt with the development of our technological genius for the production of more than adequate food, clothing, housing, and utilities for every person on earth.

Watts goes on to make a prediction — idealistic at the time, bittersweetly naive in retrospect — that “if we get our heads straight about money,” by the year 2000 “no one will pay taxes, no one will carry cash, utilities will be free, and everyone will carry a general credit card.” It’s worth noting that while some of it came true, and some might soon as we shift away from traditional currency, we have simply replaced one monetary currency with another, rather than evolving to embody Watts’s vision of redefining wealth altogether. He returns to the vital distinction:

Money is a measure of wealth, and we invent money as we invent the Fahrenheit scale of temperature or the avoirdupois measure of weight… By contrast with money, true wealth is the sum of energy, technical intelligence, and raw materials.

Considering the question of the national debt — “a roundabout piece of semantic obscurantism” — Watts argues that we go into debt, as individuals and as nations, precisely because we confuse money with wealth, the worst symptom of which is war:

No one goes into debt except in emergency; and therefore, prosperity depends on maintaining the perpetual emergency of war. We are reduced, then, to the suicidal expedient of inventing wars when, instead, we could simply have invented money — provided that the amount invented was always proportionate to the real wealth being produced…

If we shift from the gold standard to the wealth standard, prices must stay more or less where they are at the time of the shift and — miraculously — everyone will discover that he has enough or more than enough to wear, eat, drink, and otherwise survive with affluence and merriment.

Illustration from ‘How People Earn and Use Money,’ 1968. Click image for details.

And yet, Watts recognizes, there is enormous cultural resistance to such an awareness, one reinforced by our material monoculture:

It is not going to be at all easy to explain this to the world at large, because mankind has existed for perhaps one million years with relative material scarcity, and it is now roughly a mere one hundred years since the beginning of the industrial revolution. As it was once very difficult to persuade people that the earth is round and that it is in orbit around the sun, or to make it clear that the universe exists in a curved space-time continuum, it may be just as hard to get it through to “common sense” that the virtues of making and saving money are obsolete.

Understanding the distinction between money and wealth, Watts argues, would help us realize that “there are limits to the real wealth that any individual can consume” — that we can’t really “drive four cars at once, live simultaneously in six homes, take three tours at the same time, or devour twelve roasts of beef at one meal.” Acknowledging the semi-serious facetiousness of this picture, he writes:

I am trying to make the deadly serious point that, as of today, an economic utopia is not wishful thinking but, in some substantial degree, the necessary alternative to self-destruction.

The moral challenge and the grim problem we face is that the life of affluence and pleasure requires exact discipline and high imagination.

Illustration from ‘How People Earn and Use Money,’ 1968. Click image for details.

Reflecting on how easily we become habituated to comfort, affluence, and pleasure, Watts echoes Bertrand Russell’s lament — “What will be the good of the conquest of leisure and health, if no one remembers how to use them?” — and notes:

Affluent people in the United States have seldom shown much imagination in cultivating the arts of pleasure.

He paints an alternative picture for cultivating the art of leisure in its proper form — an idea glimmers of which we begin to see in the groundswell of today’s maker culture:

A leisure economy will provide opportunity to develop the frustrated craftsman, painter, sculptor, poet, composer, yachtsman, explorer, or potter that is in us all — if only we could earn a living that way. Certainly, there will be a plethora of bad and indifferent productions from so many unleashed amateurs, but the general long-term effect should be a tremendous enrichment of the quality and variety of fine art, music, food, furniture, clothing, gardens, and even homes — created largely on a do-it-yourself basis.

And yet what prevents us from truly cultivating such an economy is a fundamental disconnect. He admonishes:

Here’s the nub of the problem. We cannot proceed with a fully productive technology if it must inevitably Los Angelesize the whole earth, poison the elements, destroy all wildlife, and sicken the bloodstream with the promiscuous use of antibiotics and insecticides. Yet this will be the certain result of the technological enterprise conducted in the hostile spirit of a conquest of nature with the main object of making money.

Illustration from ‘How People Earn and Use Money,’ 1968. Click image for details.

While this problem has been tragically exacerbated since Watts’s day, it’s worth remembering that our choices — our individual, everyday choices — matter. But equally important, Watts points out, are the choices made by those who hold power in the world, both commercial and political. Noting that “many corporations — and even more so their shareholders — are unbelievably blind to their own material interests,” Watts writes:

It is an oversimplification to say that this is the result of business valuing profit rather than product, for no one should be expected to do business without the incentive of profit. The actual trouble is that profit is identified entirely with money, as distinct from the real profit of living with dignity and elegance in beautiful surroundings…

To try to correct this irresponsibility by passing laws (e.g., against absentee ownership) would be wide of the point, for most of the law has as little relation to life as money to wealth. On the contrary, problems of this kind are aggravated rather than solved by the paperwork of politics and law. What is necessary is at once simpler and more difficult: only that financiers, bankers, and stockholders must turn themselves into real people and ask themselves exactly what they want out of life — in the realization that this strictly practical and hard–nosed question might lead to far more delightful styles of living than those they now pursue. Quite simply and literally, they must come to their senses — for their own personal profit and pleasure.

What it takes to return to our senses, Watts argues, is to reconsider our illusion of the separate ego and acknowledge our interconnectedness with the world in all its material and metaphysical manifestations:

Coming to our senses must, above all, be the experience of our own existence as living organisms rather than “personalities,” like characters in a play or a novel acting out some artificial plot in which the persons are simply masks for a conflict of abstract ideas or principles. Man as an organism is to the world outside like a whirlpool is to a river: man and world are a single natural process, but we are behaving as if we were invaders and plunderers in a foreign territory. For when the individual is defined and felt as the separate personality or ego, he remains unaware that his actual body is a dancing pattern of energy that simply does not happen by itself. It happens only in concert with myriads of other patterns — called animals, plants, insects, bacteria, minerals, liquids, and gases. The definition of a person and the normal feeling of “I” do not effectively include these relationships. You say, “I came into this world.” You didn’t; you came out of it, as a branch from a tree.

It all comes full circle as we begin to see that this notion of the artificial ego is at the root of our mistaking money for wealth and symbol for reality:

The greatest illusion of the abstract ego is that it can do anything to bring about radical improvement either in itself or in the world. This is as impossible, physically, as trying to lift yourself off the floor by your own bootstraps. Furthermore, the ego is (like money) a concept, a symbol, even a delusion — not a biological process or physical reality.

Does It Matter? Essays on Man’s Relation to Materiality is a wonderful and soul-expanding read in its entirety. Complement it with Watts on happiness and how to live with presence, our media gluttony, and how the ego keeps us from becoming who we really are.”

“In 1994, Sherwin Nuland (1930–2014) — a remarkable surgeon and Yale clinical professor who in his nearly four decades of practice cared, truly cared, for more than 10,000 patients — received the National Book Award for his humanistic masterwork How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter (public library), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize that year. It is one of the most existentially elevating books I’ve ever read — an inquiry as much into how we exit this life as into how we fill its living moments with meaning, integrity and, ultimately, happiness. Four years later, Nuland followed up with How We Live (public library), addressing the art of aliveness — that spectacular resilience of which the human body and mind are capable — with equal wisdom and warmth.

“In 1994, Sherwin Nuland (1930–2014) — a remarkable surgeon and Yale clinical professor who in his nearly four decades of practice cared, truly cared, for more than 10,000 patients — received the National Book Award for his humanistic masterwork How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter (public library), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize that year. It is one of the most existentially elevating books I’ve ever read — an inquiry as much into how we exit this life as into how we fill its living moments with meaning, integrity and, ultimately, happiness. Four years later, Nuland followed up with How We Live (public library), addressing the art of aliveness — that spectacular resilience of which the human body and mind are capable — with equal wisdom and warmth.

The Backfire Effect: The Psychology of Why We Have a Hard Time Changing Our Minds

by Maria Popova

“How the disconnect between information and insight explains our dangerous self-righteousness.

…

On the internet, a giant filter bubble of our existing beliefs, this can run even more rampant — we see such horrible strains of misinformation as climate change denial and antivaccination activism gather momentum by selectively seeking out “evidence” while dismissing the fact that every reputable scientist in the world disagrees with such beliefs. (In fact, the epidemic of misinformation has reached such height that we’re now facing a resurgence of once-eradicated diseases.)

…

“In disputes upon moral or scientific points, ever let your aim be to come at truth, not to conquer your opponent. So you never shall be at a loss in losing the argument, and gaining a new discovery.”

…

McRaney traces the crushing psychological effect of trolling – something that takes an active effort to fight – back to its evolutionary roots:

Leave a comment

May 20, 2014 · 6:28 pm